Bacteria Becomes Something Beautiful

Meet the designer reimagining the possibilities of fabric dyeing

Words by Farah Shafiq. Images by Julia Moser

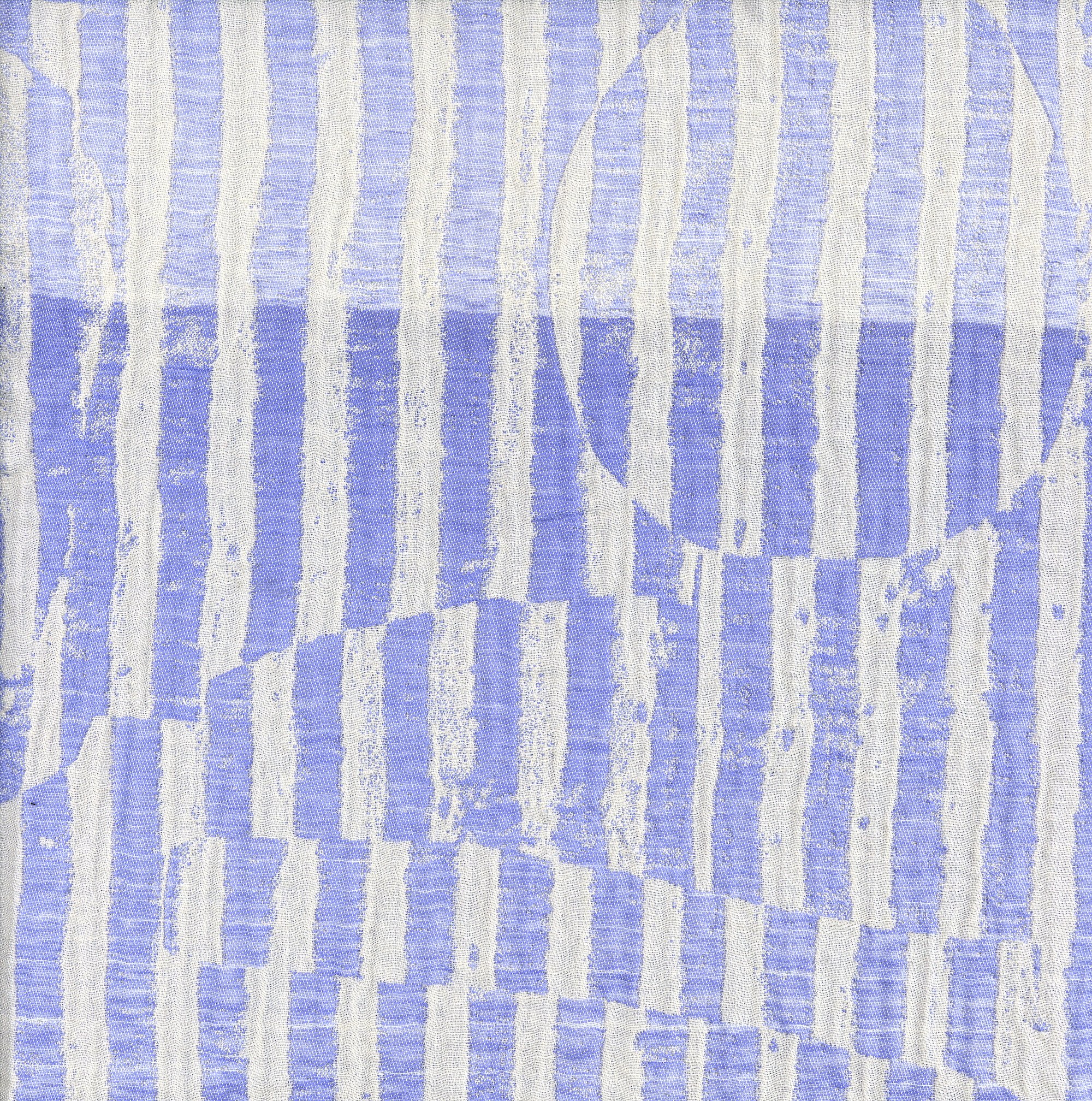

“To see beautiful things in ugly, uninspiring ones” is how Julia Moser introduces her outlook, one that informs her ongoing project ‘Growing Patterns. Living Pigments’, which sees bacteria take on an array of new forms in the name of beauty, creativity and innovation. Moser’s key motivation? “To introduce the bacteria as potential healers for the fabric dyeing industry.”

Moser is a leading light in this field, a designer who honed her skills studying textile design, art and fashion technology. She’s also an assistant at the Arts University in Linz, drawn to the city for its innovative spirit. “More and more the universities in Linz are working together, helping to create a really active ground for innovation across culture, arts and technologies,” she tells Looms, speaking over Zoom while on a break from the laboratory. [Read more about Linz’s creative energy in our interview with Fashion & Technology professor, Dr. Christiane Luible-Bär, here.]

Here, we find out exactly how bacteria became Moser’s most inspiring “co-collaborator” and how she aims to bring value to this area of innovation through her work.

When did bacteria first come into your design sphere?

As a designer and not a scientist, I always assumed bacteria innovation was something that was amazing, but probably not something that I’d work with. Then, I did a workshop that sparked so many ideas, and that was the beginning of my exploration.

Bacteria dyeing is such a wonderful sustainable technique that brings a lot of advantages – even compared to natural dyeing techniques. The bacteria grow very fast; you don’t need vast lands, many resources, any pesticides, a lot of water, or any harmful chemicals for this technique.

For me, these advantages are beautiful, because I feel very connected to the element of water. In the textile industry, it’s a resource that is needed, polluted and exploited a lot, so I’ve always been interested in preserving and using it in a thoughtful way.

Where do you source the materials you need?

Some specific strains of bacteria are sourced from databases, others I source from nature – but in those cases, it has to be categorised by specialists, otherwise it can be dangerous.

In terms of the fabrics, some are clothes discarded by hospitals. For me, it’s an interesting juxtaposition: introducing bacteria to textiles that have only seen the sterile conditions of a hospital, while focusing on a method that aims to heal the planet, too. It also involves upcycling a large amount of garments, which fits with my overall ethos.

Talk us through your process…

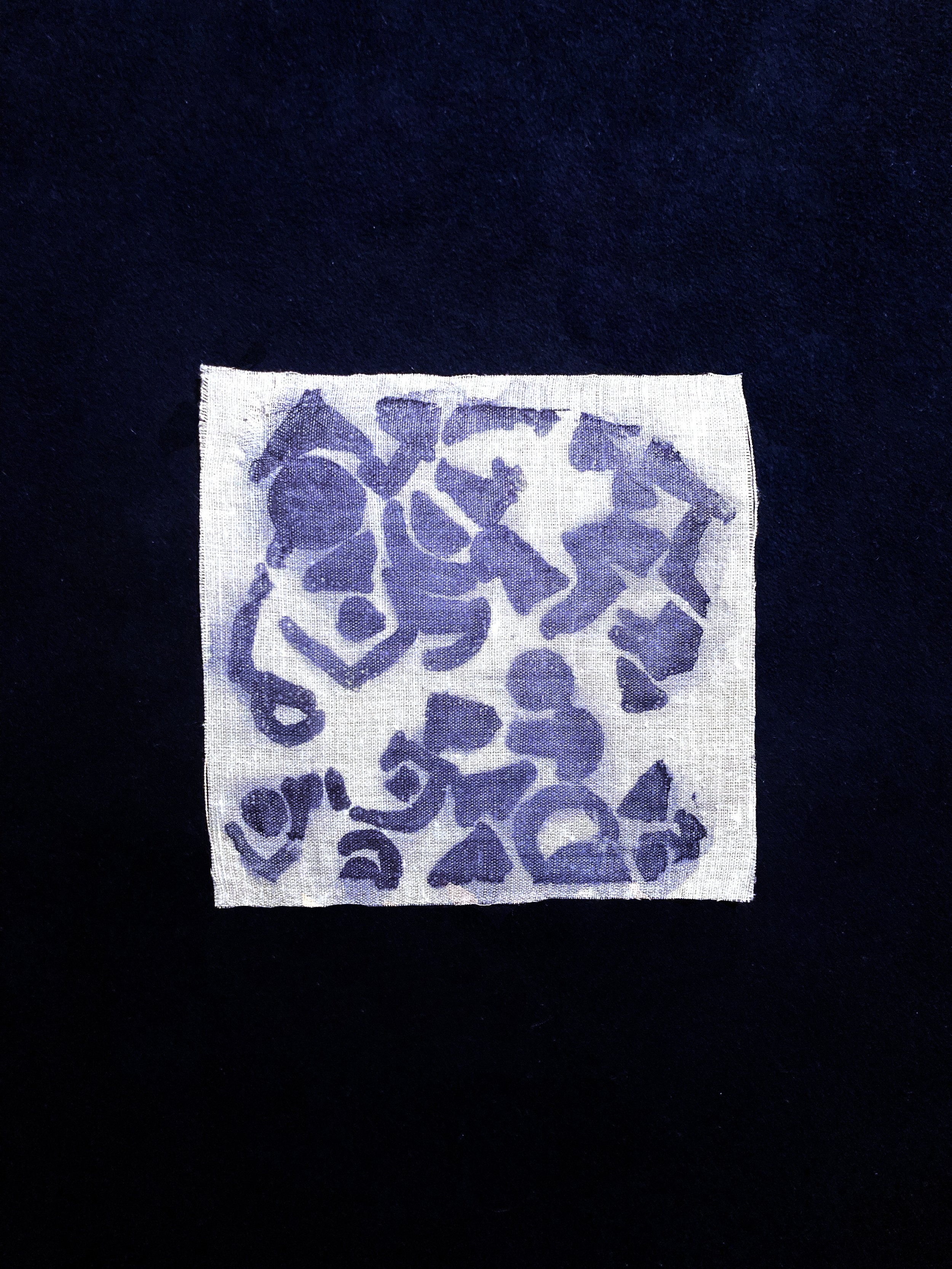

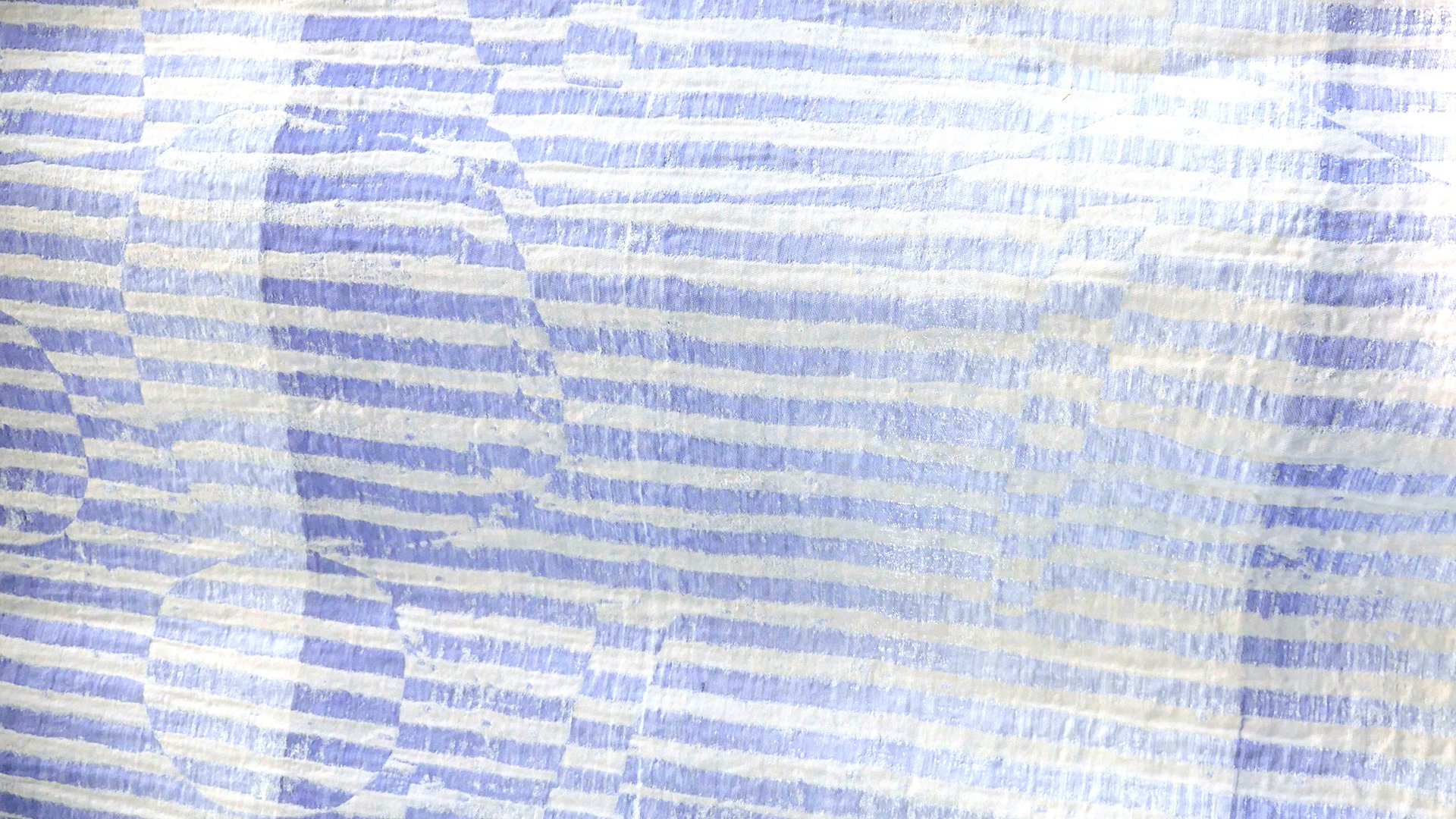

My design process is always a little bit back and forth, it’s very reactive and involves a lot of testing. At the beginning, I was focused on intentional pattern design, in response to the fact that when I researched bacteria dyeing, it was mostly about randomly grown forms on fabrics, or homogeneously dyed fabrics, which are not very precise.

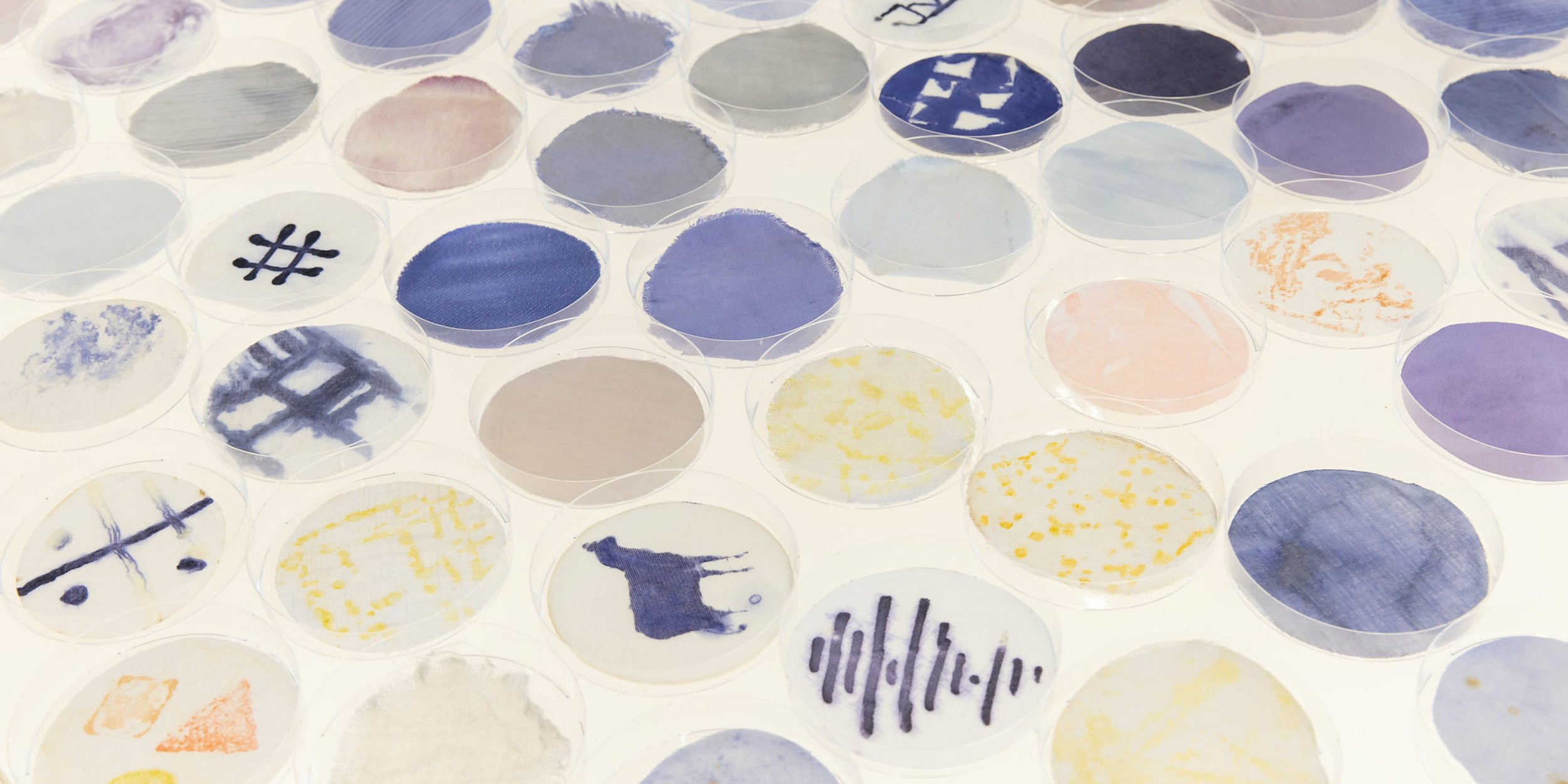

I did a series of experiments, combining bacteria dyeing with a range of materials and new technologies, such as UV and 3D printing and laser-cut acrylics for plate pressing, and traditional methods, such as weaving and knitting. The results were beautiful. I also sketched the shapes made by the bacteria and used these drawings to make the patterns for the garments themselves, creating very unique pieces.

The deeper I go into working with the bacteria, the more I see them as my co-collaborators, and as individuals. Every strain reacts in a completely different way – it’s like they are taking on personalities. While I set certain parameters, I also leave space for the bacteria to add their input. And so, my focus has shifted as the bacteria take on a greater role within the design process.

Can you tell us more about the potential of the colour strains?

Certain bacterial strains always create a certain colour spectrum that can hardly be manipulated without synthetic biology. That means that the colours are more or less set by your choice of strain. There are strains whose colour spectrum can have wider ranges – from rose to blue, for example – and there are some ways of regulating/manipulating the colours through pH-values and nutrition for the bacteria. It's not easy to create an exact tone, but my experiments have shown that there are quite a few options that allow for more accurate, intentional pattern designs.

There are always surprises, though. The combination of bacteria dyeing with 3D printed textiles has been very interesting in terms of colour and pattern, as I received stunning but contradictory results. When I let the bacteria (a strain of Janthinobacterium lividum) dye the fabric for the first time, the edges of the 3D-printed forms were much darker than the rest, creating a beautiful pattern. They reacted in the same way when I used laser-cut acrylic plates. So, I assumed that the bacteria was reacting to the filaments and materials, gathering towards the edges.

Then, I tried the same method with a different mutation of the same bacterial strain, and the results were almost completely opposite. The bacteria would not go to the edges, instead the dye was focused towards the centre of the shapes. Seeing how different strains react opens up a whole world of potential to create different shapes and colours.

What has surprised you most in your investigations so far?

I decided to formulate a way of translating the bacteria’s communications – as a metaphor for the difficulties I have faced from time to time in the process of working with and understanding the bacteria – creating a kind of alphabet. I started with a bacteria dyed piece of fabric that I scanned and pixelated, matching different letters and letter combinations to the different colour shades. Patterns emerged, and while I chose the letters, as I continued reading this ‘language’ pixel by pixel, it became a very unexpected, beautiful, reactive exchange.

I was surprised which ‘words’ came out, and how mystical the language sounded. So much so that I used it in a piece of performance art: combining spoken word, music created by correlating the shades to different notes, and a performer wearing the garments. It took place in Linz in a beautiful setting that is used for sustainable community farming. The building there has an amazing atmosphere, with incredible acoustics – and the mood was quite ritualistic and fluid, in honour of the importance of water (in the dyeing process, telling the whole story). Performance art is a direction I want to explore further, as it is a means of directly connecting to people’s emotions and creating deep feelings.

Where do you hope to take this new-method bacteria dyeing?

I think it would be realistic to scale commercially, there’s a lot of potential and I know some startups and enterprises who are moving in that direction – especially when it comes to harvesting the pigments of the bacteria, rather than working with the living organisms. It could also contribute to more circularity in the fashion industry and the creation of new solution-based business models – re-dying clothes when they fade, or switching up the colours to follow trends, giving them a new lease of life. Working with living organisms is a long process though, and sometimes difficult to control, so more fine tuning is needed.

My role is to push this method forward, with further research and experimentation, to make the technique more known to the public and to dispel the fear that bacteria is something to be afraid of. I do think there’s a shift in the good will of the consumer, as they become more open to these new methods and solutions. The beauty of bacteria dyed fabrics is in their uniqueness, which for me is much more appealing than any identical mass-produced pieces.