A Bio-Based Material World

The research and design studio constructing to heal our eco-systems

Words by Harriet Thorpe. Images by Material Cultures/Henry Woide

As long as high-carbon materials such as concrete, steel and polyurethane continue to dominate in building, can architecture ever be sustainable? What if instead, we could regeneratively grow our building materials so they could help instead of hinder the planet? Using natural ‘bio-based’ materials could help us create truly sustainable and carbon-negative architecture, though it’s going to take some hefty disruption across industries from agriculture to construction, and even politics to get there.

Regardless of the hurdles, this is the scenario that drives London-based research and design practice Material Cultures. The non-profit organisation led by architects Summer Islam, Paloma Gormley and George Massoud advocates the adoption of bio-based materials in architectural construction – meaning natural materials either grown (such as straw or timber) or abundantly found in the earth (such as clay and stone) in their raw or composite forms.

One of the materials they are most excited about is straw; the by-product of crops such as hemp, barley, wheat and oats, which is cheap and easy to come by, particularly in the UK where historically it was used for thatch roofs, among other construction techniques. Today, its most practical use in a building would be in a composite product; such as a ‘Hempcrete’ block or panel that could be used both structurally or as cladding.

Material Cultures is currently investigating how large thatch panels could be prefabricated and used in modern buildings as cladding, as well as promoting other straw-based composite building products currently on the market: from ‘Strokettes’ a light, breathable block made of chopped straw, manufactured by H.G Matthews; to ‘Inditherm’, a hemp-based insulation material that reduces the risk of damp in buildings.

Disrupting the status quo

The problem is that although these materials are just as useful and effective – even fire-resistant – as other building materials on the market, they are only being adopted by the construction industry on a very small scale. “It’s partly because the cultures, systems and supply chains around the contemporary palette of concrete, brick, imported soft wood, polyurethane insulation and rock wool are so strong. It will take an amount of disruption to the status quo for change to happen and it needs to be intentional,” says Gormley.

Her experience developing a hemp-based building product for a house in Cambridgeshire was a huge motivation for the establishment of Material Cultures. Gormley’s studio Practice Architecture collaborated with Margent Farm, a R+D facility developing bio-plastics with hemp and flax, to create a prefabricated hemp panel and design the Flat House that shows off the raw and textural beauty of the material. In doing so, Gormley developed a hankering for hemp, enjoying the straightforward design and build process and the spiritual connection to the land.

The scaled-up vision

Hempcrete became a bit of a habit, and now Material Cultures is scaling up these ideas in a housing development in Lewes, south-east England – the design of which has just been submitted for planning permission. “The intention is to build [the development] from a prefabricated cassette system that incorporates Hempcrete, very much in line with the principles developed at Flat House,” says Gormley. As well as employing bio-based materials, they are collaborating with Local Works, a studio that investigates how construction waste from the existing site can be repurposed into new building materials.

Scaling up again from housing development to a city, it is here that bio-based materials would play a key role alongside the existing infrastructure of concrete and steel, improving and repurposing it for new uses. “One part of our vision is that cities will be retrofitted with every combination of straw, cork, mycelium and all the materials that we are learning more about. So you might end up seeing terraced houses with thatched roofs in London.”

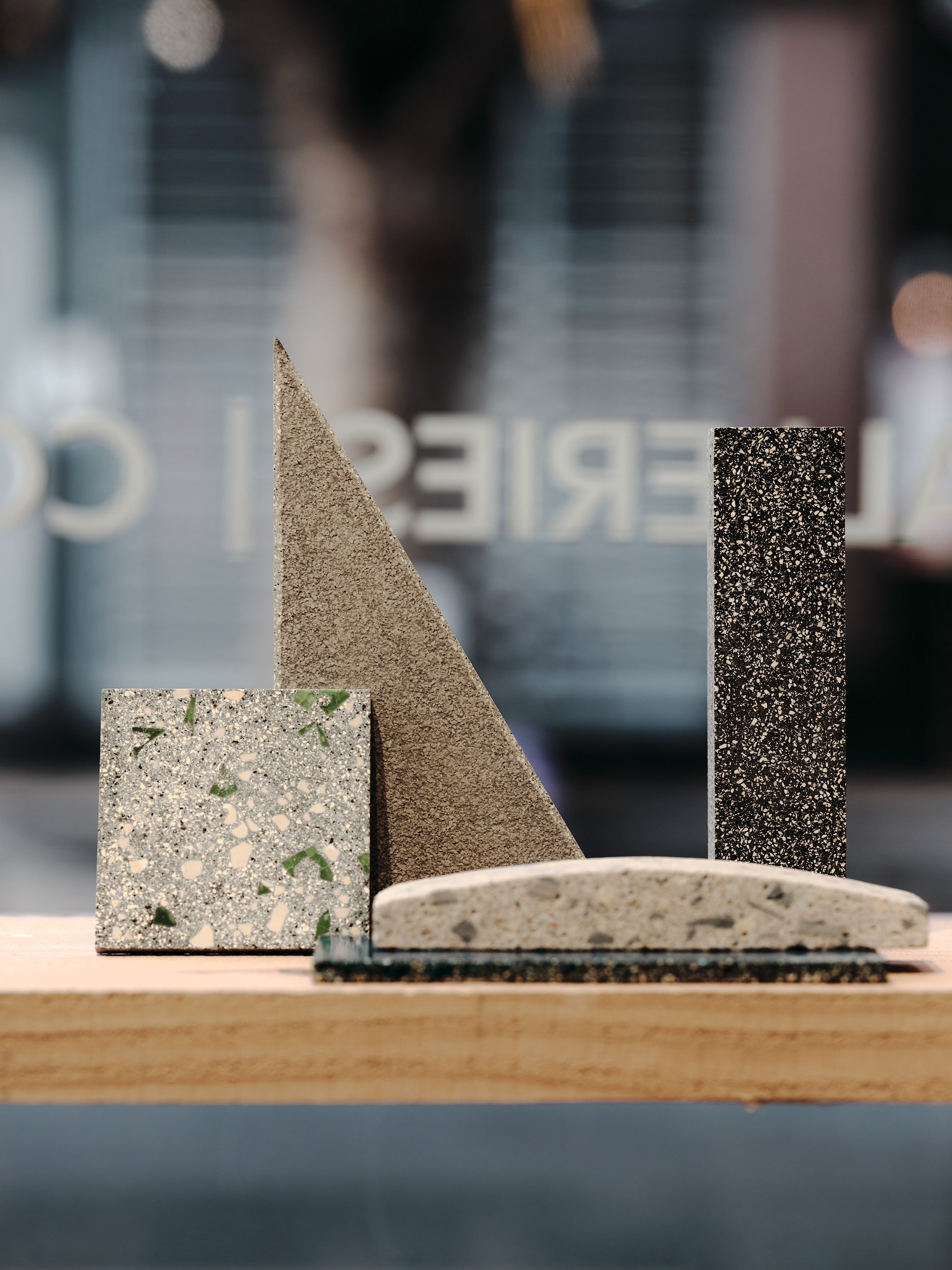

Interrogating the materials

While straw-based materials are currently less common in construction (Gormley estimates approximately 0.001% of new developments use products such as Hempcrete), other bio-based materials are very common – such as clay (in bricks) and timber. When investigating these materials, Material Cultures interrogates the unsustainable processes and practices surrounding them that need more careful consideration.

For example, the abundant natural material of clay is used widely in the UK in the form of bricks, yet the brick-firing process requires additives and vast amounts of heat that can create high carbon costs. Instead, Material Cultures advocates unfired clay products that follow a rammed earth technique closer to the ancient wattle and daub building technique.

Engineered timber too – like cross-laminated timber and plywood, harvested from trees that provide habitats and sequester carbon – is an excellent and widespread material used for structure, walls and flooring. Yet Material Cultures notes the “glues, preservatives and acetylizing chemicals” required to strengthen the wood, and the absolute requirement for timber to be harvested in a carefully-managed and regenerative way.

That’s why, as well as testing bio-based materials in architectural contexts, Material Cultures examines how they could be integrated into the complex networked system of politics and economy that surrounds the construction industry in the UK – a sprawling ecosystem of labour, supply chains, agriculture and land-use. If materials are to be grown here, reducing the carbon costs of global material transportation, it will depend on agricultural reform and combining crops for construction materials with other competing crops and land-uses, explains Gormley.

How to make it happen

The picture only gets bigger from here. “Using organic matter in the form of the building material is one of the most direct ways we can carbon capture and store,” she says. “I think that’s a critical part of what we are talking about – it's not just that using bio-based materials causes less damage, their use in construction also has the potential to be a major component in the rehabilitation of ecosystems and the atmosphere. This is effectively because we are drawing carbon out of the atmosphere and putting it into plant matter, which is going into buildings and being stored there.”

Reaching this scenario is a huge and lengthy challenge, so where to begin? “Regulating embodied carbon would have a dramatic impact,” says Gormley. That would mean that by law new buildings would have a carbon limit, so high carbon materials would have to be cut back and alternative lower carbon materials would have to be sought out. “On one hand it is devastating to reduce everything down to a metric, meaning that we fall into systems of trading, not just carbon trading but ecosystem trading, all underpinned by the growth logic of capitalism – which in a way is the problem. But, we seem to only be able to make change at a strategic structural level if it is within that capitalist growth framework.”

The regulation of embodied carbon in architecture is a matter that is currently being campaigned for and slowly moving up the agenda – if this does happen, bio-based materials are set to be big business. To keep moving in the right direction, it will require the likes of Material Culture's creative approach to materials, collaborative cross-industry spirit, and equal parts disruptive and conforming attitude – plus an industry-wide unwavering ambition for more regenerative architecture.

Material Cultures has recently released a handbook Material Reform: Building for a Post-Carbon Future (Mack, 2022)